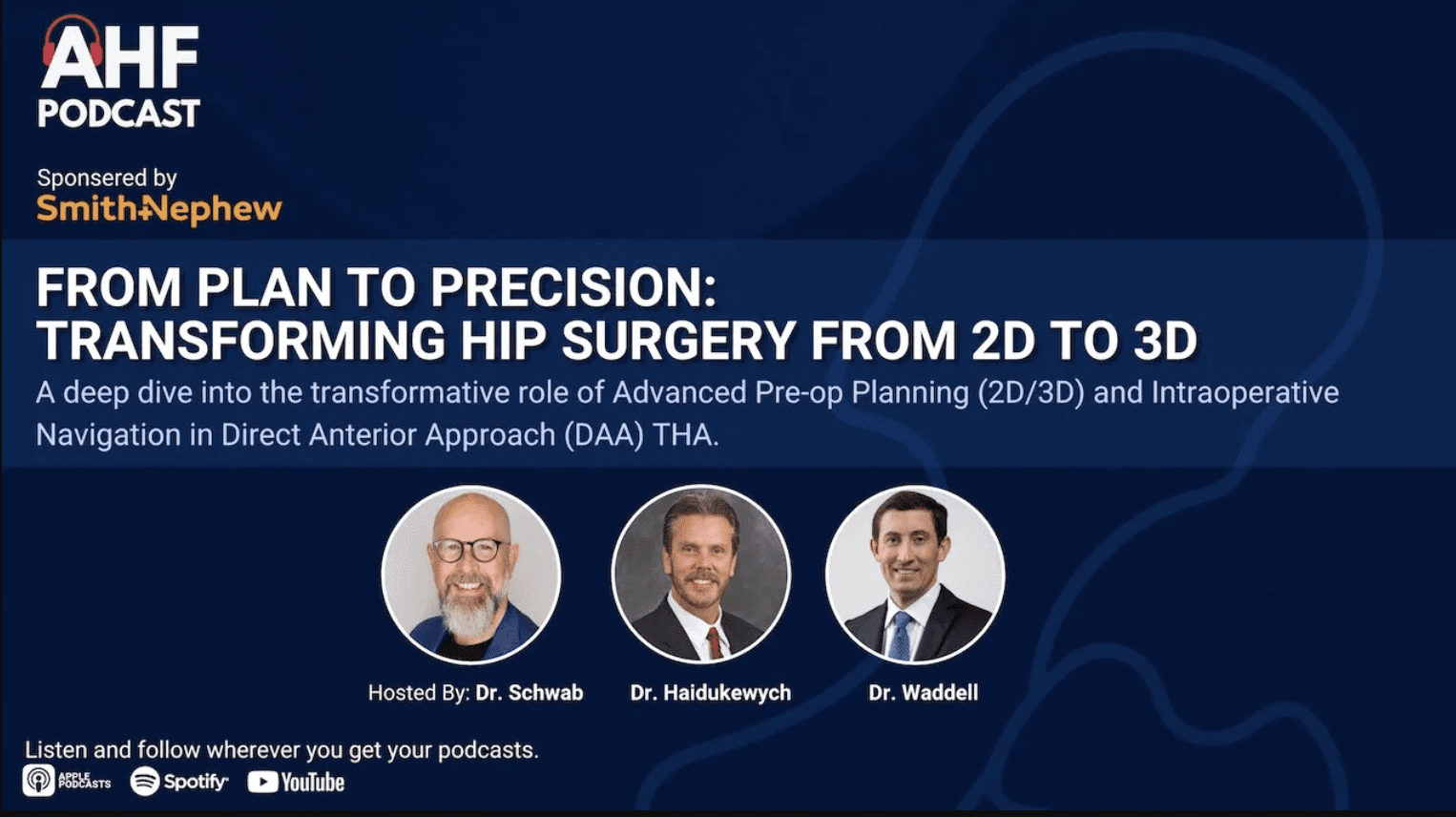

The Journey: Advancing the Anterior Approach

In this installment of Dr. Joel Matta’s Anterior Hip journey, he reflects on the challenges and breakthroughs that shaped his anterior total hip journey. In this post, he shares pivotal moments from the early days of refining the technique, the lessons learned from complications, and the perseverance required to make the anterior approach the reliable procedure it is today.

While broadly accepted today, the road to the safe, reliable, and repeatable anterior approach technique I use and advocate for was not entirely smooth! Along the way, I encountered complications—problems that needed solving. Here are some of the challenges and the lessons they taught me.

Early Challenges: Stem Selection and Operating Room Proficiency

In the early days of using the anterior approach, I paired a new cemented stem with a new cement. While postoperative X-rays often showed excellent cement mantles, I began seeing early radiolucency at the bone-cement interface in a troubling number of cases. These issues required revisions—an outcome so frustrating that I nearly abandoned the anterior approach altogether. But after careful reflection, I concluded that the approach itself wasn’t at fault. I shifted to the triple-taper polished MS-30 cemented stem, and the radiolucencies, along with the need for revisions, disappeared.

Initially, I also faced longer operating room (OR) times and higher blood loss compared to posterior approaches. However, as my technique improved, these issues resolved, solidifying my belief in the anterior approach.

Adapting Tools: The Zweymuller Stem

In 2001, I transitioned to the Zweymuller stem, which had an excellent long-term record and aligned with the growing preference for uncemented stems. Unfortunately, its design wasn’t a great fit for the anterior approach. Its straight insertion tools and lateral flare created complications, leading to fractures of the greater trochanter or proximal femur—issues I hadn’t encountered with cemented stems.

In response, I turned to Larry at the race car shop again – to fabricate custom broach handles for me. While these helped mitigate the challenges, it became evident that a different direction was necessary.

Photo from Zimmer Biomet

Refining Technique: Insights from Thierry Judet

A visit to Thierry Judet in 2002 provided invaluable insights. Thierry demonstrated the importance of dislocating the hip prior to the neck cut, a step I had not previously mastered. Unfortunately, my initial attempts at this technique resulted in three ankle fractures within two months due to overly forceful leg rotation. Adjusting the dislocation technique eliminated this complication entirely—a reminder that even small changes can have significant impacts.

Joel Matta and Thierry Judet remain in touch – this is a more recent picture taken in 2022.

Sharing Knowledge: Early Training and Challenges

By 2003, I was sharing what I had learned through courses on the anterior approach. My first course featured one ProFx table and a single cadaver, and I demonstrated Zweymuller implantation. The initial ProFx table was labor-intensive, and some participants, like me, experienced trochanter fractures while attempting the technique. Still, the approach progressed, and each challenge brought new improvements.

Transparency in Complications: Building a Culture of Learning

My background in acetabular and pelvic fracture surgery taught me to expect and address complications openly. However, when I entered the total hip arthroplasty field, I was surprised by the backlash against the anterior approach. Critics eagerly highlighted complications, often exaggerating them. The three ankle fractures I encountered during the learning phase were a frequent focus.

Despite the criticism, I made a conscious decision to report all complications, including those that occurred during the development phase. Transparency is critical—not only to prevent others from repeating mistakes but also to maintain credibility. In orthopedics, being seen as dishonest is far worse than being known for encountering complications.

Progress Through Persistence

New techniques inevitably bring challenges, but these hurdles are not insurmountable. They are problems to be solved. When a new approach shows superior outcomes in uncomplicated cases, the goal is to eliminate complications and make excellent results the standard. History offers many examples: Charnley’s pivot away from Teflon bearings, Letournel’s reduction of infection rates with the ilioinguinal approach, and more.

By 2004, I was fully committed to advancing the anterior approach, convinced of its advantages. While many established experts in hip surgery dismissed the technique as dangerous or impractical, I welcomed their opposition. Advocating for the anterior approach wasn’t my first time championing an unpopular idea—I had previously supported operative treatments for acetabular fractures, which ultimately became the standard. In the end, you can’t “win the game” if there’s no one to play against.